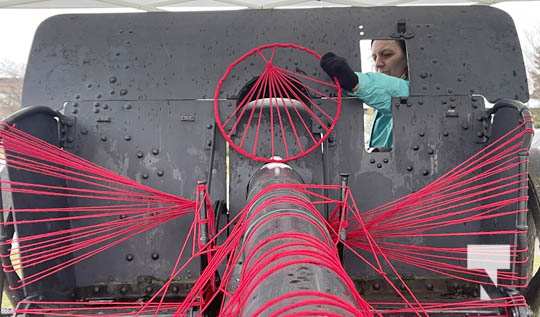

Hamilton-based Métis installation artist Tracey-Mae Chambers brought her national touring project Hope and Healing Canada to Port Hope on Wednesday, December 15, 2021.

Chambers was on the front lawn of Town Hall for most of the day, situated near the Lt. Colonel Williams statue, stitching together intricate and complex geometric designs with thousands of meters of red yarn for a live, one-day outdoor art installation. The goal of her artwork is to start conversations about decolonization and to spark hope and healing across the country. This art installation was pre-approved by the Municipality.

Hope and Healing Canada came about as a reflection upon the challenges of the current global and national climate, including the impacts left by the pandemic and the realities of past and present racial discrimination. It became further emphasized by the discovery of Indigenous children buried on the grounds of residential schools over the summer.

The installations use red yarn, which she reuses at various locations to act as a way of creating a visual and tangible image of connectivity. Each piece is different and is detailed and intricate. The installations are aimed as an act of decolonization and aim to offer hope to find healing and a way of deeper understanding.

Chambers has been creating site-specific art installations using thousands of meters of red yarn for both indoor and outdoor spaces at museums, galleries, and cities across the country. There are 74 confirmed sites on her tour so far. As her work makes its way across the country, each installation will look different depending on where it’s hosted, but the message of hope and healing will remain the same. Each of the installations are temporary, ranging from only a day, to six months.

“The red yarn represents danger and power, but also courage and love, and is also a racial slur and associated with blood and veins” says Chambers.

In her artwork, Chambers asks “Where do we go from here – individually and collectively. How do we heal and remain hopeful?”

“When Tracey-Mae Chambers reached out to us about the opportunity to bring her project to Port Hope, we were honoured,” says Debbie Beattie, Program Director for Critical Mass Art.

“Coincidentally, our curatorial theme for the upcoming year of programming is Where do we go from here, so the fit with Chambers’ project was serendipitous. We were delighted to have the Municipality of Port Hope support and pre-approve our request to have Chambers create her pop-up installation on the front lawn of Town Hall near the Colonel Williams statue, presenting a meaningful opportunity for deeper reflections and conversations around decolonization.”

“The temporary art installation for the Hope and Healing Canada project is timely as we are working on an Indigenous Awareness strategy, which will include consideration of options for the future of the Colonel Williams statue,” states Bob Sanderson, Mayor of the Municipality of Port Hope. “The statue celebrates Colonel Williams as the hero of the Battle of Batoche, suppressing the First Nation and Métis resistance. This view is challenged by a contemporary understanding of the consequences that the battle had on Indigenous communities and culture. The monument does not reflect Port Hope’s current values and we are committed to engaging our community and municipal stakeholders to help us explore options and the suitability of the statue in its current state as part of our journey toward reconciliation at the municipal level.”

Chambers said she was “offended” the municipality did not give her permission to use the statue of Colonel Williams in her art.

“The Metis artist wasn’t allowed to interact with someone this Town wants to protect. I find that highly offensive.” Chambers told Today’s Northumberland.

“Are we proud of the genocide that he (Williams) perpetuated?”

“I question why it’s not ok to touch a statue that is so offensive to me and how that can be rationalized.”

At the end of the day, Chambers did include the statue in her project without the town’s permission.

Tracey-Mae Chambers grew up as a stranger to her own story. At an early age, she was adopted and re-named, grafted into a new family tree. It was only into adulthood that her Métis culture was revealed, setting her on a new path of rediscovery. Today, the artist’s identity as an Indigenous heritage woman coexists with her interest in the natural world, both of which inform her creative practice.

Chambers’ work can be found in numerous public and private art collections across North America and Europe. She has been awarded several artist residencies, including the Artscape Gibraltar Point Residency in Toronto. Chambers is a proud member of the Métis Nation of Ontario, and her ancestors are from the Drummond Island community. She currently lives and works in Hamilton, Ontario.