By Cecilia Nasmith/Today’s Northumberland

Alderville First Nation is expecting to welcome a team from Queen’s University in the coming weeks to utilize the latest technology to determine if there are any undocumented burials of concern in the vicinity of the former Industrial School that operated within their community in the mid-19th century.

In a recent interview with Today’s Northumberland, Chief Dave Mowat not only described the operation but provided some insightful history of life in the community in pre-Residential School times.

Mowat stood in front of Alderville United Church – founded in 1870 as the Wesleyan Methodist Church – and pointed at what was the site of the community’s Industrial School nearby.

“So this is sort of like downtown Alderville at one time,” he said.

“We do know there were kids that got sick at the Industrial School like, for instance, typhus fever in the mid 1850s. So where were they buried?” Mowat wondered.

He referred to documentation indicating there were burials behind the church, “so we just wanted to be mindful of that. And now we are working on securing a research team to do some GPR work.”

The acronym stands for Ground Penetrating Radar, and this kind of work has been done in that area before.

“Maybe a generation ago, so I’m sure the technology has advanced substantially,” the chief added.

“I am highly confident there’s children here unmarked, and I would say there are unmarked communal burials.”

Constructed in 1849, the Industrial School is no longer standing, he said.

“But as far as I know, the Alderville Cemetery today – it wasn’t being used until about the early 1890s and so one has to ask: where were burials occurring pre-1890 and certainly around 1870.”

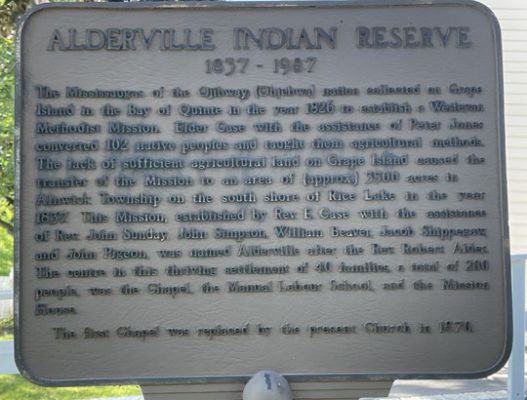

Sharing more history, Mowat said the community has been around since 1835. That’s an important date to remember, he noted, since it was pre-Confederation by more than 30 years.

“The Industrial School predates the Residential School process that we know about through TRC (the Truth and Reconciliation Committee),” he said.

“The Industrial School system came out of the Bagot Commission of 1842-1844, and what it did was advance the assimilationist agenda. But unlike the Residential School era of 1883 and afterwards, our people in the 1850s had some de facto self-governing authority and that had a determining effect on if this school would survive.

“There was probably not a lot of children that came here over the years. Some of then would run away, parents would come and get them.”

The term Industrial School is not as widely known as Residential School. Mowat offered some background revolving around the concept of division of labour.

“Women did certain harvesting activities and worked in the rice fields as well. But what the Industrial School system did was put the boys and men out in the field to learn how to be farmers and carpenters. Of course, they were already doing that at Grape Island, but this would be the tradition.

“And then the women would become quote-unquote domestic servants and take them out of the rice fields and take them away from those traditional activities and put them in the house, teach them how to be domesticized young ladies.

“Quite an assimilationist agenda.”

The Industrial School in Alderville lost the confidence of the community by the mid-1850s.

The year it had been built, there was no such thing as the Indian Act, the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, the Gradual Civilization Act, Mowat pointed out – “so our people are self-governing.

“But they were willing partners in establishing the Industrial School so that our people would not be cheated by the white man, so that they would be able to survive within the growing agrarian society around them. And that was the intent.

“But as things progressed, as the language might become targeted within the school, that did not sit well with the chiefs and community leaders and the parents.

“And again they were de facto self-governing, so they had the inherent authority to say, ‘You’re not going back there’ or ‘we are coming to get you.’

“All the communities that agreed to send their kids here also agreed to forward 25% of their annuity money to help fund the school, and so that was a sizable investment as well. And as they pulled back on that as well, that had a determining effect.”

Again, Mowat said, the key point is that it’s pre-Confederation. Then there’s post-Confederation.

“That’s where the Canadian government uses the rule of law to usurp the self-governing authorities of our people, and that’s an important timeline for people to keep in mind when we think about the Industrial School.

“It had the same designs of bringing children in and assimilating them, in essence, but the legal authority was not there.”

Mowat said that the Queen’s University team will be led by Dr. Alexander Braun.

“His name was given to me by Shane McCartney, who is an archaeologist that we consult with on archaeological assessments that take place throughout our area here and into Prince Edward County. And so I asked Shane, and he gave me the name of Alexander Braun.

“And he was all over it. He knew exactly where we are and he knew what needs to be done. He’s formulating a research team of probably master’s students and then he will come up and do the work. I’m going to say within the next month we are going to have a plan in place.”