By Cecilia Nasmith/Today’s Northumberland

It is thought in some quarters that D-Day would not have succeeded so well in hastening the end of World War II if not for the lessons learned at Dieppe.

Unfortunately, the lessons taken away from that Aug. 19, 1942, battle were costly in the extreme.

Of the 6,100 Allied soldiers involved, about 5,000 were Canadians. Only 2,200 of them would return from the hard-fought battle, many of them wounded. Some 1,950 would be taken prisoner and 918 would lose their lives – some of them dying of their wounds, either back in London or in dreadful conditions in Prisoner of War camps.

As the 80th anniversary of this tragic battle approaches, two Port Hope residents are recalling their own connections to it through loved ones who were there and would subsequently spend years as POWs.

The late Ron Reynolds, who would come to Port Hope in retirement with his wife Margaret, had gone to war with the Royal Regiment of Toronto. The two of them returned to Dieppe for the 50th, 55th and 60th anniversaries of the battle. She returned with a few family members after his death in 2010 to scatter her husband’s ashes there.

Over their lives together, Reynolds heard much about the battle from his point of view.

At that point in the war, there was concern among the Allies that the Nazis all but had the whole of Europe in their grasp. There was talk of Fortress Europe, and the U-boats they sent out were making a shooting gallery of the Allied ships on the Atlantic Ocean, Their hold on Europe had to be weakened, and a large amphibious Allied raid on the heavily fortified coast of France was devised. Code name: Operation Jubilee.

Things did not go as planned. They were spotted early, so the element of surprise was lost and the soldiers landed under heavy fire. The seawall and cobblestone beach made it difficult for their heavy machinery to move. It would become clear that a retreat was necessary, but not everyone got away in time.

“It was just a fiasco, really. It truly was,” Reynolds declared.

To her, Lord Mountbatten must take a large share of the blame. She sees him as focusing on making a name for himself with the sycophantic backing of his cohorts.

“It was just such a horrendous mess,” she said.

“Ron happened to be in the Royal Regiment of Canada, and they took the most deaths that day.”

Many of the Canadians at Dieppe were young Toronto boys of the 48th Highlanders and Royal Regiment of Canada. Reynolds had been in the reserves prior to the war (“they used to call them the Friday Night Soldiers”) and, at 21, joined the Royal Regiment that his father had been a member of before him (when it was known as the 3rd Battalion).

“He was so proud of his regiment, so extremely proud,” she recalled.

Reynolds would later hear what an ordeal his parents were put through after the battle. He was the baby of the family, the child who could do no wrong and was, in return, so devoted to them.

“They were very, very, very devoted church people until the raid,” she said.

“The first news they got is that he was missing. Of course, they were all missing – they didn’t know where they were. Then they got the news he was presumed dead, then the news that he was taken POW.

“His mother was a beautiful lady, but she wasn’t that strong. Her hair turned from dark brown to solid white. When Ron got home, he could not believe his mother’s hair.”

Even surviving to be taken prisoner was just the beginning of another kind of odyssey. Medical care for the wounded was haphazard, and many were lost to infections and complications.

And many starved to death, Reynolds added.

“The average fellow lost 70 lb.,” she said (her husband among them).

Inevitably they foraged for food. She credits her husband’s award-winning sprinting background with his success in making away with a prize rabbit, and the rare kindness of a guard who looked the other way long enough for them to have a one-time feed of rabbit stew.

The couple met after the war, when both were in the same waiting room to apply for the same job. It’s a beautiful story, she said, and it lasted 64 years.

“The day the war ended, the people like myself who worked in a war plant were told, ‘That’s it. Don’t come back. The war is over,’” she recalled.

With no government benefits like unemployment, she added, “you needed a job the next day.”

The young couple turned out to have a lot in common.

“It turns out my father guarded the German prisoners of war here in Canada during the Second World War, so they had lots of notes to compare.”

Her father spoke of so many 18- and 19-year-olds who found Canada so much to their liking that there was no thought of escape. Many didn’t even want to go back to Germany after the war – and of those who did, quite a number quickly came back to Canada.

“They were just young boys who didn’t know what end is up.”

While some Dieppe veterans would never talk about what they had been through, Reynolds was quite open with his wife. He even took an active role in the Dieppe veterans’ POW Association, glad to meet up with the others who had been in the POW camp and advocate with them to – eventually – get the benefits they felt were due them from Ottawa. It was gratifying to them that their success to some degree opened the door for the Hong Kong veterans also to get the recognition that had been denied them.

But whatever support Ottawa could give was not enough in some cases. The concept of PTSD was unknown at the time these veterans came home. When a veteran might self-medicate with alcohol, for example, his loved ones would often express bewilderment that a drinking problem should develop AFTER he had finally come through such an ordeal and had his whole life ahead of him.

They were close friends with another veteran who had made it home and lived just around the corner. He could sing like a bird, she recalled, though he would sometimes go blank on the words.

“We couldn’t believe it when we got the message he had taken his own life the night before.”

After her husband’s death, there was no question for Reynolds as to what must be done.

“I had to take his ashes back when he passed away. He wanted to be with all his buddies.”

It was an official request he had in his will, she said, but it’s something she would have done anyway. On the beach with her daughter, her daughter’s friend and her two grandchildren, they scattered the ashes and watched as the ocean bore them quickly away.

Among the many acts of courage among the Allies at Dieppe, two such acts would earn the Victoria Cross, Canada’s highest award for military valour. Both of the men were taken prisoner.

Lt.-Col. Cecil Merritt was captured as he led a courageous raid in the face of heavy resistance. Honourary Capt. John W. Foote surrendered – after a terrible day of ministering to the wounded, he gave up his place on a landing craft that could have taken him to safety expressly in order to be taken prisoner so he could minister to the many men who would be held captive.

Capt. Foote left a family back in Port Hope, including his nephew Ned Towns.

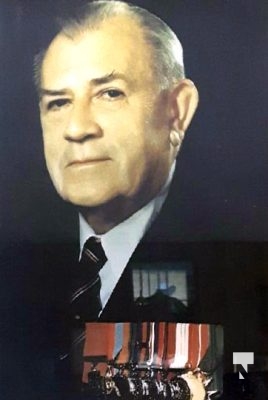

Towns has lived in Port Hope all but a handful of his 92 years, but he originally came as a child – his father had died, and his mother sent him and his brothers to live with their aunt and uncle in Port Hope. That would be John Foote and his wife Edith.

He didn’t get a chance to know his uncle very well, as he would enlist in the war effort in 1940, but he recalls the angora rabbits he was raising (and left behind for young Ned to take care of – eventually they all died, he recalled). In retirement, he bought a little farm north of Grafton with the idea of raising pheasants, though foxes put an end to that.

Foote remained in the army after the war although, when the family moved to Barrie for his posting at Camp Borden, Towns returned to Port Hope within a couple of months.

“He could have gotten out,” Towns marvelled of Foote’s courageous actions.

The beloved uncle whose sacrifice won the VC has inspired a lot of praise, including his own. Foote’s photo with his award has a place of honour in his living room. And the Grafton Royal Canadian Legion Branch 580 is also named in his honour.